Part II

In the first part of our article about brutalism in the Czech Republic, we focused on the history of the movement, some iconic brutalist structures around the country, and Viliam Chlebo’s specific contribution to the New Stage of the National Theatre in Prague – namely the T2407 series armchairs, of which we have recently renewed production. However, the construction of the New Stage itself is an interesting and tumultuous story that bears taking a closer look.

You can read more about the history of Brutalism and T2407 chairs for Nová scéna here..jpg) Draft akvarel New Stage, Karel Prager, Photo: Mariana Holá, 1980-1983

Draft akvarel New Stage, Karel Prager, Photo: Mariana Holá, 1980-1983

The birth of the New Stage

An extensive reconstruction of the National Theatre in Prague was already being discussed as far back as the 1920s, with the idea that a new structure should be built between the existing National Theatre and the Voršila Monastery. Over the years, several architectural contests were held, the last of which took place in the 1960s, which was won by Bohuslav Fuchs. The architect was highly respected in his time for his modern and international thinking. He had constructed more than 150 buildings, including, for example, the Avion Hotel in Brno and the City of Brno Pavilion. Unfortunately, Fuchs passed away in 1972, and so the project was taken over and modified by Pavel Kupka. According to Kupka’s design, three separate buildings were to be constructed: an administrative building, a restaurant, and a building with a social hall. The reconstruction was set to begin in 1977, and the project was to be completed in 1983, aiming for the 100th anniversary of the opening of the National Theatre.

Bohuslav Fuchs, studie of the New Stage, 1960

Bohuslav Fuchs, studie of the New Stage, 1960

However, in 1980, when the frames of the new buildings had already been constructed, the project was modified at the behest of Josef Svoboda, the scenographer of the National Theatre. Svoboda had gained worldwide acclaim for his multimedia project Laterna Magika, which combined live performance with recorded audio and video projections and had debuted at Expo 58 in Brussels. Svoboda was looking for a space for the Laterna Magika theatre company, and he managed to convince the National Theatre to modify the project to this end. Svoboda was a renowned visionary who combined science and art, and he was, and still is, one of the most respected scenographers in the world. But the deadline for the centenary celebrations was only three years away. If the ambitious project was to be completed on time and as planned – something many people doubted possible – it needed strong leadership, which is why Karel Prager, who was renowned for his managerial skills, was selected to head it.

Laterna Magika – Magic Circus, 1977, photo from the archive of Josef Svoboda – scénograf, o.p.s.

Laterna Magika – Magic Circus, 1977, photo from the archive of Josef Svoboda – scénograf, o.p.s.

Karel Prager, a controversial architect

Karel Prager was one of the most prominent Czech representatives of the brutalist architectural style, and to this day his buildings meet with much criticism and divide public opinion. However, this does not change the fact that he was an architect who was able to meet tight deadlines and whose ideas were ahead of his time.

Prager studied architecture at the Czech Technical University in Prague, and after completing his studies in 1949 he joined the company Stavoprojekt, where he designed apartment buildings. One of the first projects to garner him attention was his reconstruction of the Polish Cultural Centre in Prague in 1957. He used light furniture, new materials, and simple lighting fixtures in its construction, imbuing the design with a distinctive spatial transparency.

Karel Prager and Olbram Zoubek (February 1982, photo by Emanuel Křenek)

Karel Prager and Olbram Zoubek (February 1982, photo by Emanuel Křenek)

Prager’s lifelong credo was: “Architecture is the unity of time, place, and action.” This is why his projects were always thought out down to the smallest detail, combining urban planning and infrastructure and incorporating the building’s function in its design. He created buildings that were light, airy, and elegant. They featured distinctive layouts, often with circular floor plans and octagonal or pyramidic shapes. This can be seen, for example, in the Komerční Banka building in Prague’s Smíchov neighbourhood.

One of Prager’s major projects from the 1970s, which was never realised, was a structure in Prague’s Košíře neighbourhood that he called the “City above a City”. His idea was to expand the city above its existing developments in a vertical direction. He took his inspiration from Japan, where they had started with similar thinking in the 1960s. He sought to create a project that would preserve the original buildings and expand the city upward instead of outward. Unfortunately, the structure never came to fruition.

Model of the project “City above a City” Karel Prager, from the exhibition about Karel Prager

Model of the project “City above a City” Karel Prager, from the exhibition about Karel Prager

Despite all of Prager’s experience from his previous projects, the construction of the New Stage presented some unique challenges. In this case, the project involved not designing a building from scratch but rather adapting the existing, partially completed structure to fit a new plan. It was one of the most high-profile projects of Prager’s entire career, and the pressure to pull it off in time was immense.

Prager’s plan for the New Stage

When Prager took over construction of the New Stage, he was already the third different architect to helm the project, and the decision to make the building the new home of Laterna Magika necessitated a radical shift in the building’s design. Some bold and creative ideas were needed to adapt the structure to its new purpose, but the plan Prager came up with was especially ambitious. Against the investors’ conditions, he shortened the existing steel frame, and he dealt with the problem of street noise by enveloping the structure in a special double shell composed of an interior layer made of Cuban serpentinite and an exterior layer formed from a grid of glass blocks.

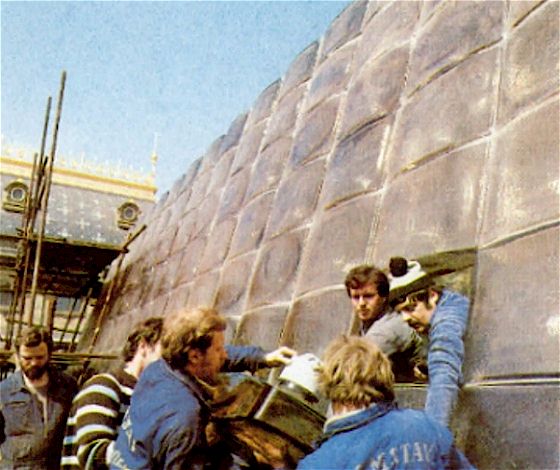

Installation of noise-proof glass facade by Ladislav Libensky and Jaroslava Brychtová, source: http://www.arch.cz/gama/

Two artists were responsible for the creation of the building’s glass façade – Stanislav Libenský and Jaroslava Brychtová. The duo had represented Czechoslovak glass art together at Expo 58 and produced various monumental objects that they referred to as “glass sculptures for architecture”. They also created the stained glass windows for St. Wenceslas Chapel at Prague Castle and the glass object Contact for the vestibule of Prague’s Národní Třída metro station. To construct the monumental relief that encircles the New Stage of the National Theatre, Libenský and Brychtová created the glass blocks using a mould for television screens. The façade comprises 4200 individual blocks, each weighing roughly 40 kilograms. In addition to reducing street noise inside the theatre, they also provide thermal insulation for the building.

Glass chandelier designed by Pavel Hlava and Jaroslav Štursa, source: https://www.narodni-divadlo.cz

Glass chandelier designed by Pavel Hlava and Jaroslav Štursa, source: https://www.narodni-divadlo.cz

Prager’s plan for the structure’s interior was equally impressive. Immediately upon entering the main building, visitors are greeted by an imposing glass chandelier designed by Pavel Hlava and Jaroslav Štursa, which hangs from the fourth floor all the way down to the ground floor, passing through the centre of the large spiral staircase. The chandelier is made up of pentagonal prisms which cast a spectrum of colours when illuminated by the neon tubes inside them.

The interior spaces of the New Stage are also clad in Cuban serpentinite (often mistakenly referred to as “green marble”). This was a particularly expensive material, but Cuba provided the stone as a way of paying off part of the debt the country owed to communist Czechoslovakia at that time.

Industrial design played a key role in unifying the interior of the New Stage, and various details such as door fittings, ashtrays, rubbish bins, and umbrella stands were all created by industrial artist Jan Tatoušek. Prager himself designed some of the furnishings as well, such as the blue, leather seats in the theatre’s auditorium. The building also features unique works by renowned Czech artists of the time, including two reliefs by Jan Simota, lighting fixtures by František Vízner, a painting by František Jiroudek, and tapestries by Zorka Smetanová.

With all of these elements together, the building forms a complete, cohesive work of art that to this day remains one of the foremost representations of brutalist architecture and design.

New Stage of the National Theatre in Prague, source: https://www.unesco-czech.cz/

New Stage of the National Theatre in Prague, source: https://www.unesco-czech.cz/

The grand opening

Despite the project’s complexity and technical challenges, under Karel Prager’s direction the construction was completed in time for the centenary celebrations. The New Stage of the National Theatre officially opened on 20 November 1983 with a production of Josef Kajetán Tyl’s The Strakonice Bagpiper directed by Václav Hudeček. The play’s staging and design showcased the technical possibilities of the new theatre, for example, by having the seats arranged in an arena-like fashion with the stage in the middle. The premiere was also broadcast on live TV.

As for the building itself, it had a mixed reception from the start, both from professionals and the public. While some praised its unique, innovative design, others found the blocky glass façade unsightly and thought it contrasted too sharply with the surrounding historical buildings, a criticism that persists to this day. However, regardless of how the New Stage has divided public opinion, in 2021 the building was designated a national cultural monument.

What’s next for the New Stage

Today, almost thirty-nine years since the building’s completion, the New Stage is in quite dire need of reconstruction, both outside and in. Parts of the building’s exterior are damaged, and the furniture, carpeting, walls, ceilings, and technical equipment in many areas need to be repaired or replaced. Reconstruction could also remedy some long-standing issues with the theatre’s acoustics. However, if these renovations are undertaken without proper respect for the original design, it could result in changes that detract from the building’s unique charm, and an important piece of Czech architectural history could be lost.

New chairs for the New Stage of the National Theatre, photo by Damian Skořepa

At Nanovo, we are strong supporters of the preservation of historic architecture and furniture, and we would like to see the New Stage reconstructed in a responsible manner. It is also out of this respect and admiration for Czech brutalist architecture and furniture that we decided to renew production of Viliam Chlebo’s T2407 armchairs from the theatre’s foyer. It is our way to pay tribute to an iconic design that has received far too little recognition and to preserve it for future generations.